New Zealand’s place names weave a rich, bilingual tapestry of references to legends and actual events, people and wildlife, heritage and origins, and to geographical or geological features. Like many countries, the abundance of place names in the indigenous language can be daunting for visitors. However, some basic guidance can remove much of the mystery and most of the challenges in pronunciation.

As the Maori people had never developed a written form of their language, much of the country’s pre-European history is the subject of spoken records, myths and legends. This results in difficulty determining exactly how long the land has been inhabited, with archaeological evidence currently roughly coinciding with stories of initial waves of Polynesian migrants arriving around 1300-1350. It is unknown if the Maori people bestowed a name upon the entire country, and several Maori names exist for each of the main islands. Today the North Island is officially recognised as Te Ika A Maui (“The Fish of Maui”) and the South Island as Te Wai Pounamu (“The Place of Greenstone”) The contemporary Maori name for the entire country – Aotearoa (the “Long White Cloud”) – is believed to have originally been one used for the North Island. Our first recorded European visitor was the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman in 1642 who put us on the world’s early maps as Nova Zeelandia, the Latin translation of Nieuw Zeeland. This was anglicised to New Zealand by James Cook upon his subsequent arrival in 1769.

Maori place names generally either describe land forms, commemorate notable events, or embrace mythology. In many cases the extreme abbreviation of events results in the name bearing remote connection to the actual events, which often leads to multiple interpretations. For example Whangarei is interpreted variously as ‘gathering place for whales’, ‘wait and ambush’ and several other meanings. One famous exception avoids any ambiguity through abbreviation to become the longest place name in the world (Taumatawhakatangihangakoauauotamateapokaiwhenuakitanatahu meaning ‘The summit where Tamatea, the man with the big knees, the slider, climber of mountains, the land-swallower who travelled about, played his kōauau (flute) to his loved one’) Reassuringly, names referring to geographical features are often concisely blunt (Pukenui meaning ‘big hill’, Waiwera ‘hot water’, Rotoiti ‘small lake’, and Wairau’s meaning of many waters is applied to braided rivers all over the country).

Other place names may infer or record past sources of food supply or other observations (Kakanui noting the abundance of a large parrot and Tutukaka referring to local opportunities to snare the same bird). Post European times also saw the introduction of corruptly pronounced or anglicised names being recorded with a bit of mish-mash thrown in for good measure (Paihia means ‘good here’), and there are a few examples of Maori imposing their own pronunciation upon the English names bestowed upon them (Poneke meaning ‘Port Nicholson’).

Pronunciation is not as daunting as it may appear. The words are constructed of short syllables with near rigid, simple rules of pronunciation. Despite this it is common to hear anglicised pronunciation of place names in routine usage, particularly in the South Island where lower population density resulted in fewer Maori place names and a lower level of familiarity with the language by European settlers.

Vowel sounds are;

Two notable consonant combinations were also used by initial British translators of the language to its written form;

Some common words encountered in Maori place names that will be guaranteed to appear in the windscreen of your motorhome are;

European explorers bestowed the first non-Maori place names upon New Zealand in their respective Dutch, English and French languages. Indeed the explorers themselves are remembered in Mt Tasman, Cook Strait and d’Urville Island. Other localities were named after their vessels or in honour of crew (examples being Banks Peninsular and Endeavour Inlet). Still others record events encountered in names such as Cape Kidnappers. The 1840s to around 1910 saw the peak period of European place names becoming established. Popular themes were the family names of early settlers (Morrinsville and Bulls) and the places they came from (New Plymouth and Cambridge) or other references to origin that are often locally or regionally prevalent (Dannevirke, Norsewood, Belfast, Bendigo, Khandallah, Glenfalloch and Duvauchelle), politicians (Seddon, Coatsville, Greytown, Greymouth and Grey Lynn) church leaders (Marsden Point and Selwyn), military heroes (Auckland and Wellington) and battles (Hastings and Khyber Pass).

Foreign politicians and royalty are also remembered – generally but not exclusively British (Cromwell, Alexandra, Mt Victoria, Queenstown and the Austrian emperor Franz Josef). Local discoverers and surveyors are recorded for their respective expeditions and achievements (the Haast, Lewis and Arthur’s Passes) Descriptive place names can also be found (Whitecliffs and Island Bay) including a handful in non English languages (Miramar being Spanish for seaview and Inchbonnie Gaelic for beautiful island)

A resurgence in recognition of the country’s heritage and indigenous language since the 1970s has refreshingly seen many examples of previously universally used English names being retired in preference for returning to their original Maori names. Mt Egmont having reverted successfully to Mt Taranaki is an excellent example. In other instances previously accepted misspellings of Maori names are being corrected (Parahaki to Parihaka for example).

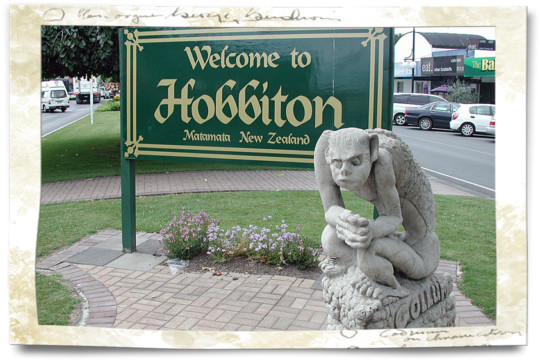

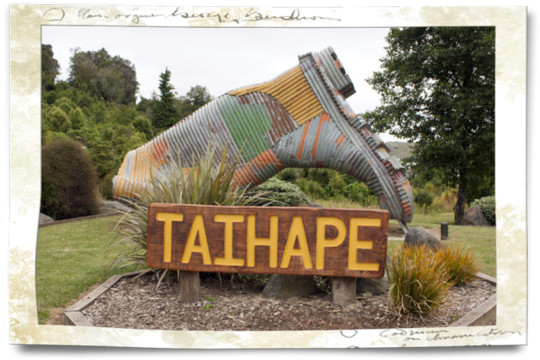

Some places have acquired widely used quirky variations of their names with popular examples based upon abbreviation (Gisborne being ‘Gizzie’, Palmerston North ‘Palmy’, Paekakariki ‘Pie Cock’, Paraparaumu ‘Paraparam’ and Taranaki ‘The Naki’). Occasionally there are attempts to add a touch of glamour that usually incorporates local influence (Rotorua becoming ‘Rotovegas’ and Wellington ‘Wellywood’). As elsewhere, mottos and local features are sometimes embraced in widespread usage (Auckland is known as the City of Sails, Christchurch as the Garden City and Wellington as the Windy City). Contemporary influence can also be found with popular reference to Hobbiton and the nation as Middle Earth. A humorous generic ‘Maori’ name for small rural townships is Waikikamukau (why kick a moo cow)

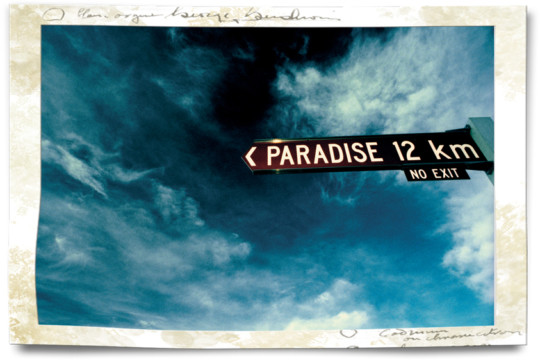

As Kiwis we also often refer to our country as God’s Own Country, or simply as Downunder – terms also embraced by our neighbours in Australia. Here at New Zealand Frontiers we prefer keeping it simple with the term Paradise and experience shows that most of our visitors from abroad (and the inhabitants of a tiny settlement at the head of Lake Wakatipu) tend to agree.